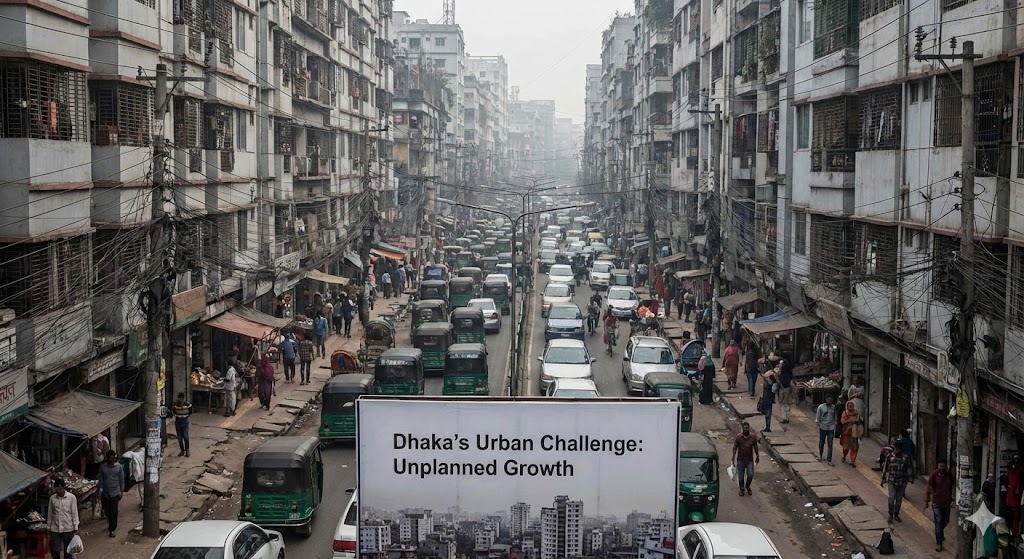

Dhaka has become one of the fastest-growing megacities in the world, yet its physical expansion has taken place with limited coordination between planning authorities, developers, and design professionals. What we see today is not merely congestion, but a deeper architectural and urban crisis shaped by fragmented decision-making. Unplanned urban growth has transformed neighborhoods into dense clusters of buildings where light, air, privacy, and accessibility are compromised. This is not just an architectural concern; it is a humanitarian issue affecting everyday life for millions.

One of the most visible consequences is the extreme lack of breathing space. Buildings are often constructed to the maximum allowable limits, sometimes even violating setback rules. Streets that were once designed for local access now struggle to support heavy traffic. Emergency vehicle access becomes difficult, waste management systems become overburdened, and pedestrian safety is neglected. The architectural quality of many areas deteriorates because design decisions are driven by short-term financial gain rather than long-term livability.

A key issue is that many projects are designed in isolation. Developers focus on maximizing floor area, while architects are often pressured to deliver visually attractive façades rather than holistic spatial solutions. The result is a city where buildings do not communicate with each other. There is little consideration for how shadows fall on neighboring structures, how wind moves through streets, or how public life can flourish between buildings. This disconnection gradually erodes the social fabric of communities.

Another serious concern is the disappearance of public space. Playgrounds, community courtyards, and small green pockets are being replaced by parking areas and commercial extensions. Children grow up without safe outdoor environments, elderly residents lose spaces for social interaction, and the mental well-being of city dwellers suffers. Architecture, which should enrich daily life, instead becomes part of the pressure.

Despite these challenges, there are hopeful directions. Many young architects in Bangladesh are now advocating for context-sensitive urban design. Concepts such as passive cooling, internal courtyards, shaded walkways, and mixed-use community spaces are gaining attention. Rooftop gardens and vertical greenery are also emerging as practical tools to restore ecological balance within dense urban environments.

For meaningful improvement, policy and professional responsibility must work together. Stronger urban design guidelines, stricter enforcement of planning regulations, and early collaboration between planners, architects, and engineers can gradually transform the way cities grow. Dhaka does not need more buildings; it needs better relationships between buildings, people, and the environment. The future of Bangladeshi cities depends on shifting from quantity-driven construction toward human-centered urban architecture.